A “late twentieth-century neologism”?

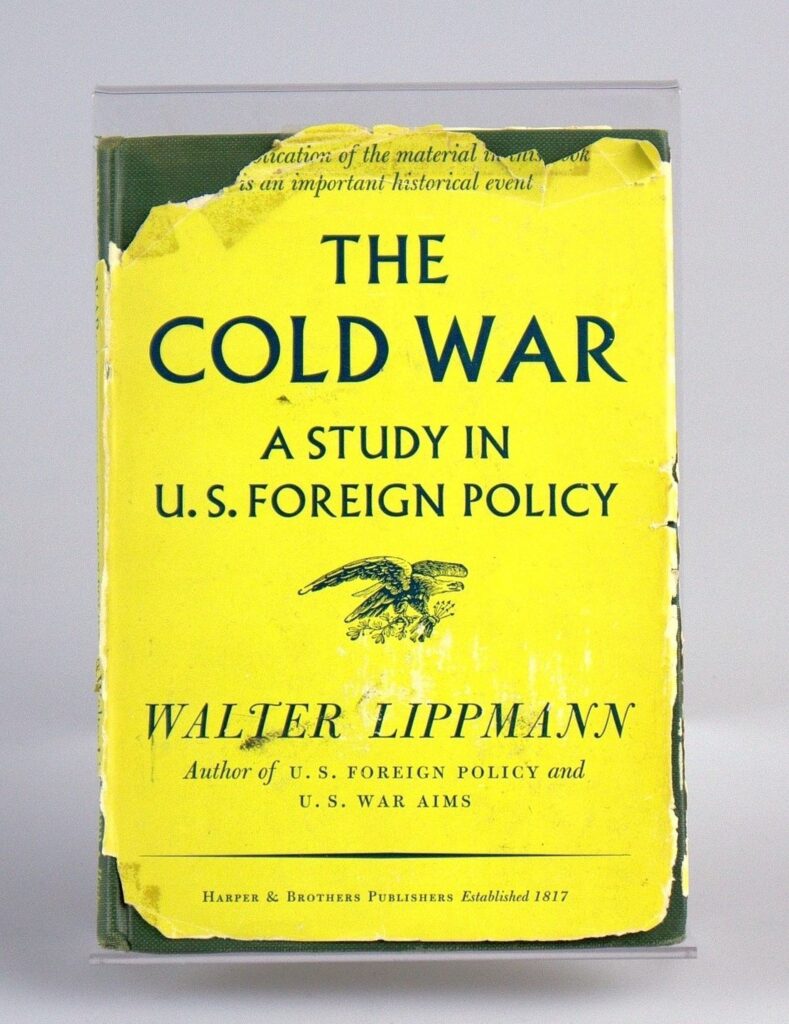

In early September 1947, the renowned political commentator Walter Lippmann published the first in a syndicated series of fourteen news columns under the common title “Cold War”. The columns would be published in a book that same autumn: The Cold War: A Study in U.S. Foreign Policy. Lippmann’s usage of the term “cold war” is notable, as only from this moment did it attain popular deployment as the name for the emergent conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States which would last until 1990.

Lippmann, however, was not the first person to use the term. Just months earlier, for instance, in April 1947, the financial magnate Bernard Baruch gave a speech in which he singled out “Russia” as the lone resistor to the American “way of life” and quest to reign as a “global guardian of safety”: “Let us not be deceived,” continued Baruch, “we are today in the midst of a cold war.” Multiple sources thus credit Baruch with coining the term, though technically the credit should go to his speechwriter, Herbert Bayard Swope.

Others, however, reject either Baruch or Swope as coiners. The eminent historian of the Cold War Odd Arne Westad instead awards this distinction to the British writer George Orwell. In his October 1945 essay You and the Atom Bomb, Orwell described an emerging post-war order in which “two or three monstrous super-states, each possessed of a weapon by which millions of people can be wiped out in a few seconds…would probably prevail in a state which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of ‘cold war’ with its neighbors.” The atom bomb, then, given its enormous cost and technical sophistication, was “likelier to put an end to large-scale wars at the cost of prolonging indefinitely a ‘peace that is no peace’.”

Further readingOrwell therefore anticipates with considerable insight and trepidation a world-order which, while ostensibly post-war, moves not towards peace but instead into a wholly new and uncertain period of indefinite standoff under the constant threat of mutually assured destruction. Westad thus plausibly classifies “cold war” as a “late twentieth-century neologism” which didn’t exist “prior to World War II.”

Close

The (sort of) Middle Age origins of the ter

Orwell’s invocation of “cold war” is clearly notable, as he is the first to use it to describe the emerging Soviet-American antagonism at the outset of the atomic age. Nevertheless, he too was not its coiner. Indeed, some even root the term’s origins as far back as the 14th century when the Spanish political commentator Don Juan Manuel purportedly used it in reference to the indefinite conflict between Christians and Arabs in Spain. However, while Manuel’s conceptualization bears a certain similarity with Orwell’s (the notion of unending conflict with uncertain results) he actually makes no mention of la Guerra fria – cold war – but rather uses the phrase la Guerra tibia (in modern Spanish, tivia), meaning tepid, or lukewarm war. The former term appears for the first time only in an 1860 republication of Manuel’s work, an apparent result of editorial discretion.

The “cold war” and the arms race

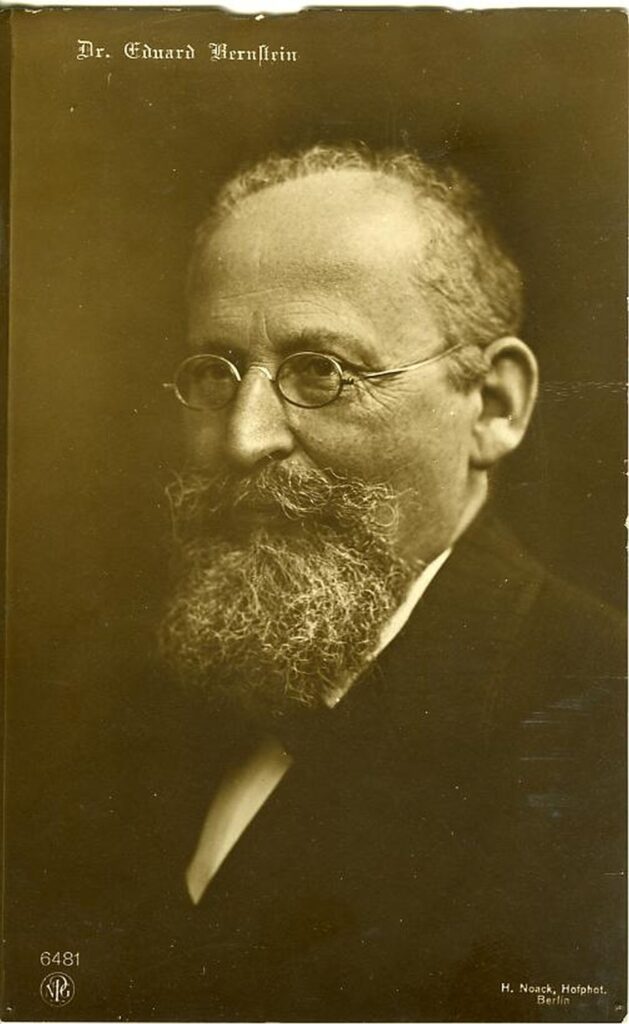

The year 1860, then, is the earliest date (so far discovered) that the term “cold war” appears in any language. Given this rather accidental usage, however, it makes more sense to credit the German socialist theorist and politician Eduard Bernstein with having first used the term. Writing in 1893, Bernstein criticized the tit-for-tat arms race underway between Imperial Germany and her fellow Great Powers of Europe: “I don’t know if the expression has already been used, but one could call it cold warfare. There is no shooting, but there is bleeding.”

And then in May 1914, mere weeks before this “cold war” would indeed turn hot, Bernstein, now a Social Democratic member of the Reichstag, used the term once more: “We continue this silent war, this cold war, as it has been called, the war of armaments, the outbidding of arms.”

Further readingBernstein’s use of “cold war” to characterize the arms race preceding the First World War thus shares something crucially in common with its application to the Soviet-American conflict. The anticipation of an arms race between the two super-powers is apparent in the western press essentially from Victory/VE Day onwards, an anticipation which would only increase following the US dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. “An arms race to end all arms races,” to quote then US Senator Brien McMahon, was on the horizon.

Close“white war” and “cold war” …

Ultimately, though, this account of the term’s origin is still incomplete. The gap between 1914 – Bernstein’s latter usage – and 1945 – Orwell’s invocation – is a considerable one, and needs clarifying. A good starting point is a 1950 exchange of letters between Walter Lippmann and Herbert Swope, in which they shared with each other how they had first conceived of “cold war”. Lippmann maintained that it was not Baruch’s speech, but rather the recollection of a pair of French expressions from the 1930s, la Guerre froide (“cold war”) and la Guerre blanche (“white war”), that had first given him the idea. Swope, for his part, said he had thought of the term as early as 1939, believing it to be a fitting contrast to the looming prospect of “hot war” – that is, actual war – and denied ever hearing such French expressions.

Though clearly at odds, both Lippmann and Swope rightly root the term “cold war” in the period immediately preceding World War II. Lippmann’s account is especially plausible, as indeed the sister-term “white war” – referring variously to “economic war,” “propaganda war” or “simply bloodless war” – is present in both English- and French-language publications throughout the 1930s, and especially towards the end of the decade.

Further readingHowever, more than simply inspiring the term, or ideas like it, the situation in Europe in the late 1930s was indeed referred to on a few occasions as a “cold war”! The first mention of the term in this period, and, moreover, the first so far uncovered in the English language, appears in an unauthored editorial published by The Nation Magazine on 26 March 1938, titled Hitler’s Cold War: “Just as Hitler has shifted his strategy at home from open terror to cold pogrom, so he may now complete the conquest of Central Europe by the process of cold warfare” – the threatened choking off of Czechoslovak trade is the specific “process” referred to here.

Another notable usage of the term comes right on the eve of war in the summer of 1939. In consecutive editions of The Atlantic Monthly the British economist and politician David Graham Hutton published two essays – “The Next War” and “The Next Peace”. Here, the term “cold war” receives arguably its most substantive pre-war conceptualization. In speaking of “the current kind of ‘cold war’ or ‘hot peace’” Hutton, like Bernstein, emphasizes the weight of the European arms race, one which has attained “astronomical dimensions”: “they have only got by without shooting, but not without war.” And just as Orwell laments those “tyrannical weapons” – not just the atom bomb but also “tanks, battleships, and bombing planes” – so too does Hutton observe how “our twenty years’ of progress in instruments of death” had severely restricted the possibility to make a “real peace” – one in which “we maintain both peace and democracy” – as opposed to “an armed peace (which is no peace)”.

CloseMaking “the term a term”

“After the next war in Europe,” Hutton concludes his essay, “America may be called upon to reopen the Old World. America – or Russia…The outcome of whatever happens in between them, in Europe, will determine their own destinies; and this whether it is war or peace – or neither.” This brings us back to Lippmann. Writing two years after “the next war in Europe” had reached its end, Lippmann’s columns focus their attention precisely on the possible fates of this devastated continent, arguing for the Marshall Plan as a first step towards “European Unity” and the eventual expulsion of all foreign armies from Eastern Europe, Germany, and Austria.

Lippmann’s first release of the “Cold War” series would appear in newspapers throughout the United States and the world beginning September 2nd, 1947. As the subsequent columns of the series were published over the next weeks, their effect on making “the term a term, a historical and political term,” as the historian Anders Stephanson put it, was quickly apparent. To demonstrate: “cold war” makes its first appearance in The New York Times on September 7th, The London Times on September 15th, and The Wall Street Journal on October 8th. And on November 11th the article “Kalter Krieg?” could even be read in the pages of Die Neue Zeit in the Soviet occupation zone of Berlin.

The “New Cold War”

To recap. We have shown that the term “cold war” – though emerging as a historical term to describe the American-Soviet antagonism from roughly 1947 to 1990 – has a pre-history, so to speak, rooted in the lead-up to the two World Wars on the European continent in the first half of the 20th century. Under the weight of arms buildups, economic pressure, propaganda campaigns, and the like, a situation prevailed which was neither peace nor war, though with a constant anticipation of eventual bloodshed.

To conclude. One need only glance at the headlines of today’s press to see that “cold war” has a post-history, too. Talk of a “new cold war” refers primarily to the rise of China as a great power – Orwell’s third “monstrous super-state” (though back then merely a “potential” power). Indeed, we can read of a new nuclear arms race between the US and China, with China’s latest hypersonic missile test even recalling for many the “Sputnik moment”. But the “new cold war” is not without its updated lexis and paradigms. The latest “Nuclear option”, to quote Radio Free Europe, concerns not weapons, but the threat to expel Russia from the SWIFT (that is, Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) electronic payments system should she invade Ukraine [EDIT: unfortunately, in the time between the writing and publication of this paper, Russia has of course done just that, while speaking of the “nuclear option” in a more literal sense. If we needed any reminder, “hot war” also lives on to the present, and – just as in the 20th century – often concurrently with its cold variant].

More generally, notions of “hybrid war,” “cyberwar,” “information warfare” and, most recently, “grey zone conflict” – defined by one US Special Operations journal as a zone of conflict “between the traditional war and peace duality” – suggest the new spaces in which the “new cold war” may already be being waged.

_______

“The cold war reaps its victories quietly.”

The Nation Magazine, 26 March 1938.

Written by Frank Mello Morales